Let’s start today off with a thought experiment, a series of inquiries not so different from the famous trolley problem.

You, a doctor, was to face a man with cancer. You heard him before you could see him, the all too familiar gurgle he made in his sleep, his body no longer had the strength to produce a strong enough cough to get rid of the buildup mucus and saliva. You approached the man and raised his head, turning it to the side so that gravity drained the secretions. By this stage of the disease, he would be spending more time asleep than awake, and he was used to your hand, your presence. Today, however, he woke, as if sensing something. Perhaps in your thought you tensed up your fingers. Perhaps you couldn’t hide your thumping heart. Whatever the case, he turned and stared at you.

You, doctor, but to him, Death, was asked

How do you do, Doctor.

This wasn’t a question. It was heavy with realization and acceptance. It wasn’t what he wanted to ask, but it sounded the same as

How long do I have left?

The fact that he avoided the subject, meant he had Hope. Perhaps he might not even let you speak at all. He might go on to recite his mantra: how he will study harder when he gets out, how he was going to graduate with his classmates, how he will become a Doctor, like you, to save people, like you.

The question is:

At what point do you stop him, to tell him he has three weeks left to live?

Or

Do you not stop him at all? Do you give him Hope?

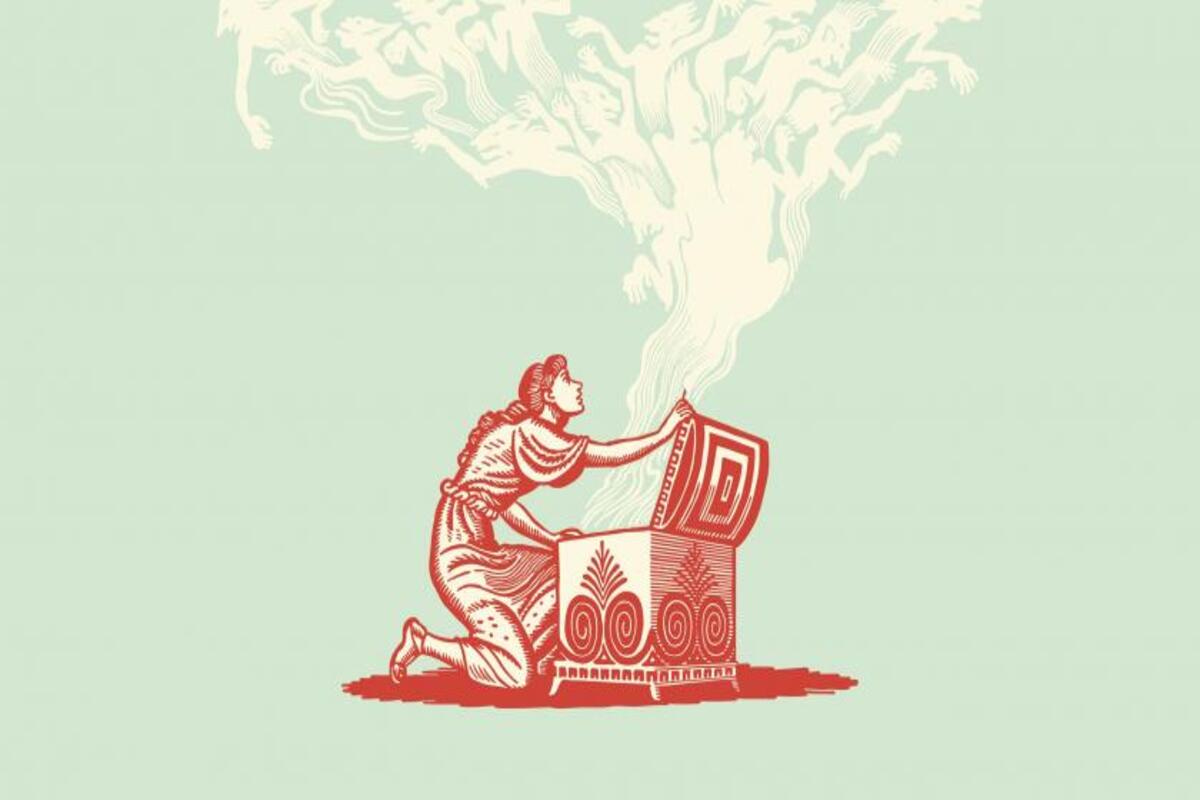

In his book Human, all Too Human, Frederich Nietzsche, whom I discovered had some similar lines of thought with myself, sees the myth of Pandora’s Box a bit different. His version of the myth sticks with the same story beats: Pandora, the first woman on Earth, was given a box (originally a jar) that said “Do Not Open.” What can more entice a human? And thus, Pandora opened the box, and all the Evils of the world, from brussels sprouts to the live-action adaptation of Dragon Balls to pharmaceutical companies to politicians… were loose, forever free to do men injury day and night. In the original, Hope the Goddess, was what remained, and is often viewed as men’s last vanguard against Evil.

According to the German philosopher, however, from that day forward, mankind was cursed with “the worst of all evils.” Why has Nietzsche condemned Hope so? Because to him, as long as Hope remains in men’s possession, he would continue to endure the other evils. It is the siren that plunges ships into the depth, the apple that forever evicts us from Eden, the pizza fresh out of the oven, threatening to burn the roof of our mouths again and again. We, in our moment of weakness (hungry at 2a.m in the morning), reach for it anyway.

[Hope is] the pizza fresh out of the oven, threatening to burn the roof of our mouths again and again. We, in our moment of weakness (hungry at 2a.m in the morning), reach for it anyway.

What, then, does Friederich Nietzsche advocate? For if we are to dismiss Hope, is Life no better than the Inferno that Dante would traverse? Should “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” be etched to the Gate of Birth, not Hell? What’s the moral of the story? To Nietzsche, I suppose, the constant need to reach for the leftover of Pandora’s Box when things go awry render a man weak. One that constantly takes refuge in an illusion of the goal will never achieve said goals. He has lost the battle before it even began. More contemporarily, men have intentionally applied an Instagram filtered to Life, covering the meaningless, illogical, machine of chaos that she is.

In contrast, by keeping the Box sealed, by abandoning Hope, Nietzsche wants us to truly carpe diem, to affirm the Life we were given and take pleasure in Life for Life, rather than any made-up versions of her.

To illustrate this point, let’s turn back to our patient for a moment, who is becoming ever more bewildered as to why you are staring in blank space. This man’s Life is fading, are you going to take his Death from him too? By offering him Hope, sustaining his illusion, you further blur him from the harsh reality that will come. There is no chance of a miraculous recovery, no chance of avoiding the pain he will have to endure the weeks before his eventual demise, all so he could keep “good spirit,” all so he could make more promises he will break. Or will you give him the choice to face the abyss head on? Will you allow him to say his goodbyes properly, to say the things he has been saving just for his death, to go through his stages of grief and choose to be thankful or hate Life. Or as Nietzsche himself would say “The final reward of the dead - to die no more.” Of course, these are mere philosophical ideas, abstraction as best. Fact of the matter is, in front of you is a flesh-and-blood human being. Who can say he is weak for wanting comfort after his battles? Who determines what is weak and strong?

Easier said than done, isn’t it Nietzsche? The philosopher was also a writer, and I bet, like myself, he had Hope. I dare not compare my scribble with Nietzsche’s talents, but more on the emotional turmoil he must have gone through while writing. As soon as I started any new project, even a short story, or a Note on Substack, I find myself tingling with excitement that “this would be my big break.” And each time I did, I spiraled deeper into self-loathing and self-doubt as I peered the less-than-desirable results. Friedrich, a self-proclaimed genius, frequently assumed that the time to understand him was yet to come, perhaps after one or two centuries. Is that not Hope?

Or perhaps, it was to Friedrich, a man of so much talent and devotion to the art of writing, that such a Hope is reasonable. Perhaps the philosopher wasn’t shunning all Hope, but only ones that blinds men from reality. Perhaps my Hope as a writer should be to have readers, not to be the next J.K. Rowling. His hope as a cancer patient should be a painless journey to Death, not being cured. Our Hope should be to stop eating pizza at 2a.m, not for the pizza to stop being hot right out of the oven. We are urged by Nietzsche to face the Evils of Life, but he offered us no weapon against which he called “the worst,” but a suggestion for us to run away from it. It seems to me to Hope is not an Evil to defeat, but one to live with, to learn about, to manage.

Next time, on Truth and Writing.