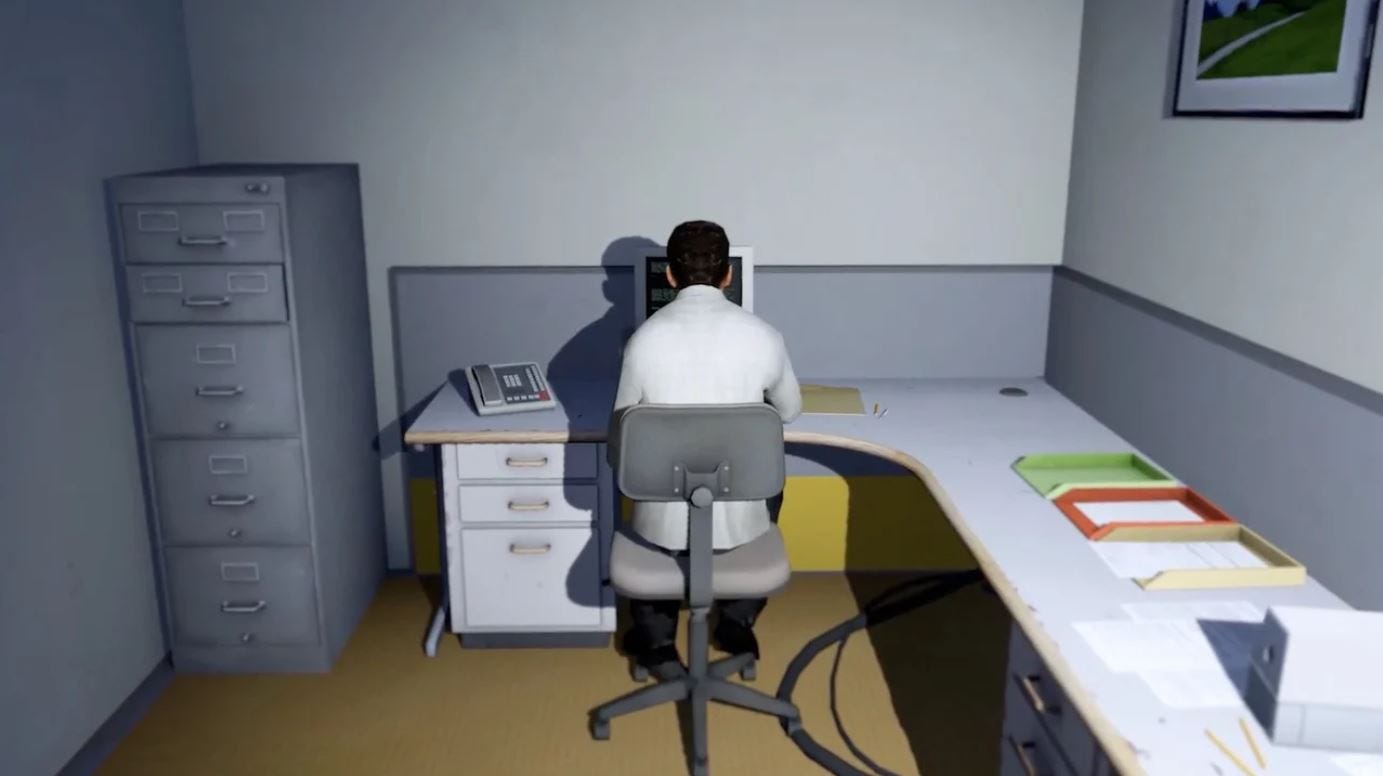

Alden Greve arrived at the office three minutes early. He always did—not from discipline or anxiety, but because the time between arrival and commencement was a quiet interval where nothing was required of him. He would sit at his desk, straighten the mouse pad, align his pen parallel to the monitor, and wait.

In the corridors of Bureau C, early arrivals weren’t remarked upon. Punctuality was not a virtue; it was simply expected, like paper in the printer tray or fluorescent lights humming overhead.

Alden processed Form 41-Bs. No one remembered when he began doing this. He had no training documents, no onboarding records. He had a lanyard, a desk, a nameplate. That was sufficient. His job was to verify that the forms conformed to themselves—boxes ticked, margins respected, occasional notations checked against past notations.

When forms were complete, he placed them into a grey tray labelled “FORWARDS.” They disappeared.

Each day, Alden reviewed around ninety-six forms. Occasionally ninety-seven. Once, years ago, he had processed one hundred and one. He remembered the number but not the day.

The office had no windows. Only the suggestion of time, marked by an institutional bell that rang faintly from somewhere else, cuing lunch, then the end.

One day, the forms changed.

They were still Form 41-Bs—at least in shape and content. But the font was narrower. The paper heavier. The guidelines were printed with more confidence, more certainty in their own necessity. Alden stared at one for several minutes, trying to articulate the difference. There was no obvious error. It simply felt less... provisional. More finished.

He looked up. Paul, in the adjacent cubicle, continued tapping without pause.

“Have the forms changed?” Alden asked.

Paul didn’t stop typing. “Not that I’ve noticed.”

Alden nodded and resumed. There were ninety-six to complete.

At home, things had been shifting, though not enough to demand attention. His wife, Marla, no longer asked him questions when he came in. She greeted him with the same smile each night—pleasant, efficient, sufficient.

One evening, she offered him a glass of mineral water. “You prefer bubbles now,” she said.

“I don’t think I do.”

She gave him a curious look, the kind you give a guest who’s eaten dinner with you before but now claims allergies. “Well,” she said, “you always finish it.”

He did. She wasn’t wrong.

Their son, Elliot, had grown in the way all teenagers do—suddenly and vaguely resented. Alden noticed that Elliot had stopped calling him Dad. Now it was just: “Can I have the keys?” or “Do you need the car?”

Sometimes Elliot brought home a friend who bore an eerie resemblance to himself—same hairstyle, same deliberate slang. They shared headphones and expressions, laughed at jokes Alden had no access to.

One night, as Alden reached across the dinner table for the salt, Elliot flinched slightly, just slightly, like a cat who’s learned caution. Alden paused, holding the shaker mid-air.

“Something wrong?”

Elliot shrugged. “Didn’t think you’d do that.”

Alden put the salt down. “Do what?”

But the moment had already dissolved.

The next morning, Alden’s security badge didn’t unlock the door. The light blinked red. He tried twice more, then waited until someone from Accounting arrived and let him in with a smile that didn’t reach her eyes.

At his cubicle, someone else was seated. Same chair. Same screen. Same desk plant—a peace lily he hadn’t watered in two weeks.

The man looked up. His face was... familiar. Close. Close enough.

“Sorry,” Alden said. “I think you’re in my spot.”

The man glanced at the nameplate: Alan Greve.

“Been here five years,” the man said. He smiled helpfully. “Must be a mix-up.”

“I’m Alden.”

The man tilted his head slightly, as if hearing a word that had fallen out of use. “Maybe check with Admin.”

Alden did. Admin directed him to Records. Records sent him to HR.

The HR representative—a woman with an indecipherable accent and impeccable posture—opened a file on her screen. “Alan Greve,” she said, pronouncing the name slowly, as if teaching it to him.

“No. Alden.”

She squinted. “I’m not showing that name. Are you sure you’ve got the right department?”

“I’ve worked here thirteen years.”

She offered a practiced smile. “And we’re very grateful. Alan’s performance metrics are exceptional.”

She stood up, walked around the desk, and placed a hand on his shoulder. “Why don’t you take a few days off? Reset. Let the system catch up.”

Alden nodded. He didn’t argue. He wasn’t upset. He wasn’t sure what he felt.

At home, he tried to explain it to Marla. She was in the middle of polishing wine glasses.

“There’s another man at my desk.”

“Did you report it?”

“They told me his name is Alan.”

“Well, maybe it’s temporary.”

“He said he’d worked there for five years.”

Marla shrugged. “Maybe you’re confusing things. You haven’t taken a sick day in years. It’s probably burnout.”

Later, she asked if he would mind sleeping in the guest room for a few nights. “You’ve been... unsettled. Just till you feel more like yourself.”

Alden stood in the doorway. “I feel exactly like myself.”

Marla didn’t reply.

The guest room was smaller, but familiar. Once Elliot’s nursery. Then storage. Now a quiet corner where Alden lay and tried to remember his own handwriting. He couldn’t.

He picked up an old journal and flipped through the entries. There weren’t many. The handwriting looked controlled, cautious. A few pages in, he found one that read:

Don’t forget the margins. The rules are the only way to be invisible.

He didn't remember writing that. But it sounded right.

By the end of the week, no one in the building recognized him. The receptionist called him “Mr. Grove.” A new ID photo was issued with a different face—still his, but slightly better. More symmetrical. Sharper lines.

He stopped going.

He still woke up at the same time each morning. Still left the house, nodding to Marla as she stirred sugar into her tea. She rarely looked up. Elliot had stopped coming down for breakfast.

Instead of work, Alden rode the trains. He watched men in suits, carrying identical attaché cases. He watched women with identical brows, sipping identical coffees from cups with meaningless adjectives—Bold. Bright. Balanced.

At one station, he saw a billboard with an ad for the Bureau. It showed a man standing at a desk, smiling at a form. Efficiency you can see. Precision you can trust.

It was him.

He stared at the image for a long time. No one else noticed.

Months passed, or maybe it was weeks.

Alden no longer minded being mistaken. When people called him Alan, or Grove, or “sir,” he answered without correction. It was simpler. Easier to move among them as a surface. The interiors were gone anyway.

He stopped speaking unless spoken to. He stopped wondering about Elliot’s expressions, or the curve of Marla’s half-smile. He dreamed of lines, margins, paper that stacked perfectly to the ceiling.

He returned to the Bureau once. Not as an employee—just to look. Through the glass door, he saw Alan—his better, his echo—reviewing forms with calm focus. The peace lily had recovered. There was a new tray marked “ARCHIVE.”

Alden watched for twenty-three minutes. Then he left.

He now lives in a long-term hotel. The walls are pale grey. The hallway hums. There is no mirror in the bathroom, but the television always works.

He receives one envelope each week: a blank Form 41-B.

He reviews it, ticks the boxes, signs the bottom.

He does not question where it goes.

And he arrives three minutes early, every time.