Turns out, I have a lot in common with Frederich Nietzsche

Getting to know you, the readers, by offering myself.

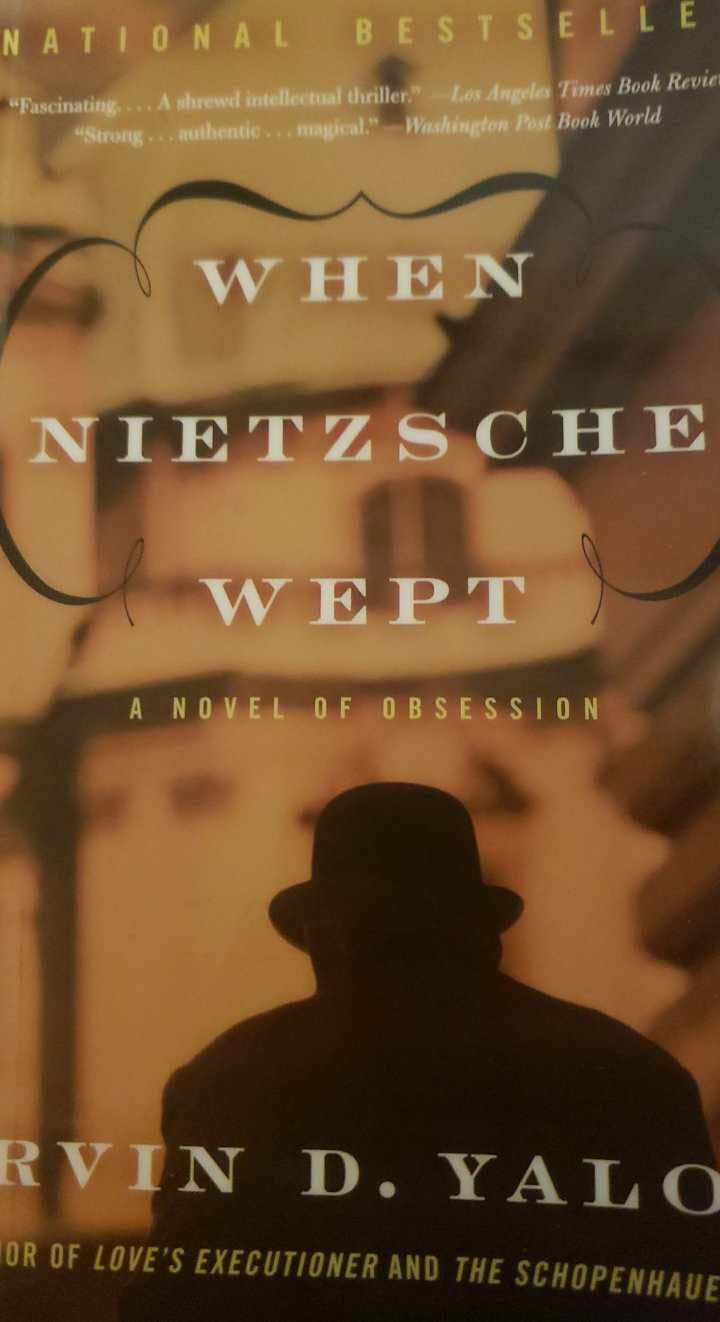

The title is quite misleading: the “things in common” I have with German philosopher Frederich Nietzsche is hardly because I am familiar with him or his views. My knowledge of Nietzsche was limited to his majestic moustache that appeared on most textbooks. The proper title should be “Turns out, I have a lot in common with Irvin D. Yalom’s view of Frederich Nietzsche,” but that wouldn’t catch anyone’s attention.

Yalom’s “When Nietzsche Wept” talks about a hypothetical scenario where Josef Breuer worked on Nietzsche’s depression and in turn, developed the “talking cure.” If you see any movie with a therapist, a sofa, and a patient lying on said sofa, you have Breuer to thank. The book won’t immediately strike your interest, especially if you don’t know who the mentioned figures are. The book continues this if-you-know-you-know premise for a quarter of the pages, with Sigmund Freud also making an appearance. I, too, found the book a slog, each page about Breuer’s life as a physician dragging me down like quicksand.

Then, he encountered Lou Andreas-Salomé, Nietzsche's friend and the source of his malady (even the great falls to love), and said

“Nietzsche is extraordinarily sensitive to issues of power. He would refuse to engage in any process that he perceives as surrendering his power to another […] No one desires, he believes, to help another: instead, people wish only to dominate and increase their own power.”

That statement didn’t just strike a chord, it plays a whole orchestra inside of me.

The first words I have written in English is my in own journal, describing that day’s happenings. One word that was repeated seventeen times in two paragraphs was

boring

And the day was anything but. Dated 20th of March, 2010, it was the usual woke up, school, being scolded for not paying attention, being scolded for talking too much, cram school, pretending to understand the materials, home, being scolded by my parents, and at the end, write journal. Shakespeare, I was not. But I blame my young age, rather than my lack of any meaningful vocabulary. The reason why I decided to write in English on that particular day came from a sneaking suspicion that Mẹ was snooping around my desk. Can’t blame her for that, since I’ve been skipping school for almost a month by faking stomach problems.

Translated from Vietnamese

19th March, 2010

This was it: the end of my ploy. The school has informed my mother that I would be suspended if I am absent for more than 30 days. It’s the 28th day. Mẹ and Ba had been through my bag, and they found the apology letter I was supposed to give Ba for a signature, but instead my own sloppy imitation was at the bottom. It wasn’t the sole reason why I faked being sick, but it played a big role: coming back to school, facing my head teacher and friends after that embarrassing attempt at forgery was something I’d rather die than do, but facing suspension was something worse than Death. Vietnamese death row inmates would happily accept the gallows than being suspended.

An epiphany was reached at that moment. My parents’ shouting and tongue-clicking didn’t induce the effect they were expecting: I wasn’t ashamed of my actions. In contrast, I was angry. I was an inmate, to the boring educational system, to the responsibilities of being birthed. They put me in a cage, and allowed themselves authority, power, over me, looking down upon me, deciding my future, Pavlov’s Dogged me into flinching when I hear of grades, tests, homework, disappointment, older brother.

No longer. That 28-day reprieve had given me a taste of freedom, and I was not going back without a fight. So, I took Ba and Mẹ’s words literally. “Do you know how much we have put into raising you?”

Translated from Vietnamese

$250.000, or roughly 6.000.000.000 vnđ, to raise a child from infant to 16.

I was an early adopter of Nietzsche’s ideas without realizing it.

Why did my parents raise me? Why go through the trouble? Is it because they have a responsibility for bringing me into this world? If it is responsibility, should it be theirs and theirs alone? If I didn’t ask to be born, why do I have to return their seemingly voluntary act with my own obligations?

Did they care for me because they wish to dominate me? And

Why do I have to listen to them, to take care of them, to get a proper education, to work at Ba’s company, to give them power over me? Why do I have to fear the elders, instead of respecting them? Is it because I owe them money? Is it because I haven’t made as much money as the adults? If I do, what will happen?

Young me didn’t know the answers, but he did have a plan. The quickest way to make money and get out of the house was to study programming.

“When Nietzsche Wept” picked up the pace after Breuer met face-to-face with Nietzsche for the first time, and subsequently hating his patient’s stubbornness to accept help. Nietzsche, a firm believer in his philosophy of power dynamics, saw any form of assistance as a compromise to his belief in the will to power. And when Nietzsche said “any,” he meant “any:” from Gods to societal norm, to even his family. In fact, by the time they met, Nietzsche had quit his job, had not been in contact with his mother and sister for quite some time, and was on the last leg of his retirement fund, all for the purpose of maintaining his fierce independence and commitment to his ideals.

I was more fortunate than Nietzsche, and less courageous. After the revelation, I would again ask for money from my parents, and stayed with them for another two years until I passed my entrance exam into high school and was officially kicked out of the house. Or, to be more precise, I kicked myself out of the house. There was no drama, no fanfare, no “I want to be a writer!” “No, you’re gonna work at your dad’s or you’re out” moment. I just packed my bags and left.

My passion as a writer comes a bit later, when I read Neil Gaiman’s American Gods for the first time.

To be continued.